Aviation stands out among different transportation modes because of its excellent safety performance achieved through continuous improvement. That includes the commitment of states to investigate accidents and serious incidents, not to allocate blame or liability, but to identify opportunities and recommendations for future prevention. However, the aircraft accident investigation system is presently inconsistent, with many states not being able to launch an effective and efficient investigation. This article discusses aspects relating to safety investigator training by highlighting its importance through ICAO USOAP audit findings.

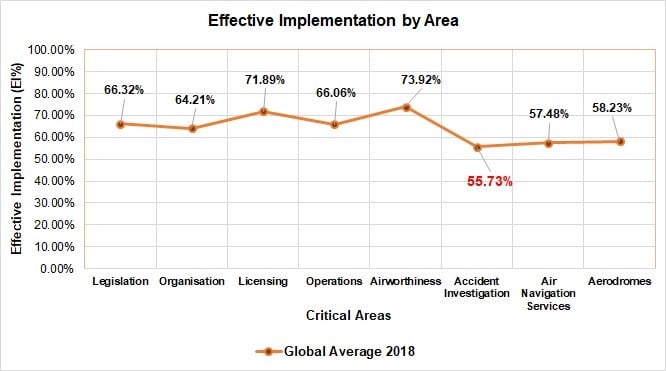

The global average level of compliance with ICAO Safety and Recommended Practices (SARPs) for air accident investigation is approximately 55%, which means almost 80 states lack the capability to establish their accident investigation system (ICAO, 2017). Some challenges related to the training of investigators persist. Despite the availability of guidance material, such as ICAO Circulars 298 and 315, some states have not yet established formal training systems for investigators. Moreover, the identified deficiencies which affect the investigation’s credibility highlight the challenge states have in ascertaining the best practices to keep the appropriate preparedness of investigators to perform the required investigation tasks (AIG Secretariat, 2008).

Figure (1) Effective Implementation by Area - Source: (ICAO, 2018)

Generally, the importance of training is highlighted by human reactions based on their observations. Individuals usually act in light of their abilities and skills developed via training, practice and on-the-job gained experience. Concerning the role of human failure, people usually react to standard circumstances by applying the known rules effectively demonstrated in such familiar and well-known situations (Stoop and Roed-Larsen, 2009). In recognising this, the European Union, for example, included in its regulation (996/2010) on the investigation and prevention of accidents and incidents in civil aviation, in article 7, the establishment of the European Network of Civil Aviation Safety Investigation Authorities (ENCASIA). It was emphasised in establishing this network that "it shall encourage high standards in investigation methods and investigator training" (Arnaldo Valdés and Comendador, 2011, p.793).

Nevertheless, we can ask, why it is important to identify and establish new training guidelines to maintain the capability of safety investigators?

Poor training of safety investigators may affect both states with low and high rates of accidents and serious incidents. The credibility of the state accident investigation agencies could be threatened if inadequate attention is given to the training of safety investigators. Safety investigators must exhibit a wide range of technical skills which need to be associated with the required abilities. These may need to be applied infrequently but on a massive scale. The challenge that many accident investigation agencies face is how to maintain the technical proficiency of safety. This could be more visible in states that have a low rate of accidents and serious incidents.

Consequently, such states’ investigators are unable to practice the job and gain the required knowledge. Even by ensuring the availability of scheduled training programmes for investigators, the outcomes of maintaining their ability - i.e currency - are not guaranteed, especially when dealing with accidents involving high levels of complexity. Other options, such as participating as observers in another state’s accident investigation, may benefit them up to a certain level but are not as good as practising the job and becoming familiar with changes at the system and subsystem levels. Accident investigation agencies are dependent on the professionalism of their safety investigators to succeed in conducting reliable and effective investigations. This is fundamental to them complying with their national and international obligations. However, such dependence may be questioned if there is insufficient emphasis on investigator training to ensure long-term success, independence and continued technical excellence.

Safety investigators in many accident investigation agencies are coping with significant work overload. With the time pressure to handle their assigned tasks, looking to the other side of the equation, the conclusion may be that; safety investigators are at risk of burning out. Most of their time is dedicated to solving clues behind a number of investigations of growing complexity and many highly integrated systems. This leaves not much time for necessary training. For instance, this was the case within NTSB when it was audited at the end of the last century (RAND Corporation, 2000). In their cognitive psychology work, Svedung and Rasmussen (2000) highlighted three levels of decision making: the person’s talent, rule and knowledge-based level. This may help to understand the nature of decisions and errors made by safety investigators, which may be influenced by their level of training.

In addition, unlike experts in the other aviation disciplines, who have the time and opportunity to continually develop and increase their technical abilities, safety investigators often only benefit from limited and fixed-training programmes. This may have been seen as not enough to prepare them to handle complex accidents. On-the-job training that is used in most accident investigation agencies is often focused on traditional accident investigation skills - "tin-kicking" - rather than new skills such as dealing with advanced technologies, software or materials. Therefore, the lack of professional development in specific technical areas and the limited time left for training create a general decline in investigators’ professional technical abilities.

Global air transport is experiencing remarkable growth. For example, private and commercial aircraft fleets that many accident investigation agencies have to deal with are changing significantly. In some cases, safety investigators only become familiar with the complexity of new equipment when an accident occurs. In addition, because of the high technology used in the new generation of aircraft, such as Boeing 787 or Airbus A350, and the new systems installed in such state-of-the-art aircraft, the expertise of safety investigators gained through the investigation process for previous generation aircraft may not be considered enough to conduct the required investigation effectively. Therefore, it becomes essential for safety investigators to work closely with several parties such as manufacturers, regulators and operators to become far more aware of the design and operation of modern new-build aircraft.

Accident investigations are increasingly time-consuming tasks, which require a different arrangement of investigators’ abilities. Comparing the amount of training that different roles in the aviation industry receive, safety investigators’ level of training is quite restricted in terms of workload, financial support, opportunities, and limitations. Safety accident investigation agencies are required to re-look at their investigator’s training programmes to maintain their safety investigators’ capability. Moreover, looking at the training guidelines for accident investigators published within Circular 298 in 2003, ICAO might have to contemplate revision to ensure those investigation agencies remain able to address the dramatic changes that have occurred in this field. The guidelines for future training should have a diversity of topics to boost investigators’ technical proficiency that may heavily influence the quality of accident investigation agencies in the near- and far-term. The training that safety investigators receive should not only cover fundamental investigative strategies. Indeed, it should cover an expansive multidisciplinary routine coordinating the unpredictability of the systems that they will be asked to examine.

The last message can be drawn as safety investigators are in need of more frequent (recurrent) training to maintain their proficiency. This is the only trusted way to ensure the continuous improvement required to maintain their technical skills is achieved.

The Safety and Accident Investigation Centre at Cranfield University offers an extensive range of continuing professional development (CPD) short courses, many of which can also be used towards our postgraduate qualifications. Our courses provide insight and knowledge to support accident investigators. Find out more.

References

AIG Secretariat (2008) AIG RELATED DEFICIENCIES IDENTIFIED DURING ICAO AUDITS: Working Paper presented by the AIG Secretariat to ICAO Accident Investigation and Prevention (AIG) Divisional Meeting (2008) - AIG/08- WP/20. Montreal, Canada: ICAO.

Arnaldo Valdés, R.M. and Comendador, F.G. (2011) ‘New European Union Approach to Civil Aviation Accident Investigation and Prevention’, Journal of Aircraft, 48(4), pp. 1396–1404.

ICAO (2017) USOAP Continuous Monitoring Approach (CMA) website. Available at: http://www.icao.int/safety/CMAForum/Pages/default.aspx (Accessed: 12 March 2017).

RAND Corporation (2000) Safety in the Skies: Personnel and Parties in NTSB Aviation Accident Investigations. Santa Monica, CA.

Rasmussen, J. and Svedung, I. (2000) Proactive Risk Management in a Dynamic Society. Karlstad, Sweden: Swedish Rescue Services Agency.

Stoop, J. and Roed-Larsen, S. (2009) ‘Public safety investigations - A new evolutionary step in safety enhancement?’, Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 94(9), pp. 1471–1479.